Anne’s Review: Wow. Love this one—hard to believe we haven’t come further in 700 years! Women are the N@$?!&s of the world, as John Lennon famously said.

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

From The Feminist Quarterly, January 2021

Me when I get a new bookI like to read. I speak a little Spanish, so I enjoy reading books in Spanish. Though I have read a couple of contemporary novels, my repertoire has generally been children’s literature (shorter and easier to digest). At the beginning of January, I decided to expand my literary experience by buying some books of short stories, classics meant to stretch my knowledge of Spanish literature and my vocabulary.

*

Ye olde villageWhen I started reading the first book, I was dismayed that the starting short story hailed from the early 14th century. That’s a ways back. If I attempted to read a story written in the English language of say, 1320, I might not catch on to everything the author wished to convey due to antiquated words and old-timey ways of saying things. Nuances are tricky enough in a foreign language. I dreaded experiencing that conundrum in my inauguration into Spanish classics. However, having read the title of the first offering, I was convinced I could make it through unscathed, or at least not as flummoxed as I had initially anticipated. The publisher of this collection included an English translation with each story. Cool.

I launched into a story by Don Juan Manuel, who was a rich guy who wrote stories based on the folklore of Spain, meant to enlighten and entertain. The title suggested to me this was a story about a man who married a strong (fuerte), brave (brava) woman. The nature of this topic perked me up a bit. The narrative went like this:

There was a poor, but good man who had a grown son who was just like him (poor, good). There was another good man in the same village who was rich but had a nasty daughter (she was grocera). Hmmm. I had to look that one up, because it didn’t seem, in my estimation, to fit with the title. Grocera = rude. I was thinking at this point the poor gal was horribly misunderstood and the plot will twist to vindicate her from this epithet.

The good son reports to his father that he is tired of being poor. Instead of leaving home to seek his fortune, he wants to marry a rich girl. I start to have a bad feeling about this guy. The lazy bastard is a good young man? In fact, he wants to wed the grocera daughter of the rich man in the village. His dad, unable to talk him out of it, goes to the rich man and states the good son’s desire. The rich dude says he would be a terrible friend if he allowed the marriage to happen, the daughter would probably kill his son. (Slayed by rudeness?) The young woman in question is not included in this conversation. So, in early 14th century Spain, a rich man and a poor man are supposedly friends. I’m not buying it. But after some convincing, the rich man acquiesces and allows the wedding.

Treasured friend?They marry. No mention of the grocera daughter or any antics one might expect from a rude woman forced into marriage, but maybe her marital prospects had not been as forthcoming as she had hoped. When left alone for their nuptial dinner, the good son sits down at the table. He wants to wash his hands, so orders his dog to fetch him some water. (If you are squeamish or even skeptical in nature, you may want to skip to the ending paragraph.) The dog, being a dog, ignores him or maybe, being given some attention after a long day of neglect, gives the young man a lick. But doesn’t bring water, so the demanding young man pulls his sword and chops off the dog’s head. Shocking.

Somebody call PETA!

He then commands the cat to bring him water, which of course the cat, as cats are inclined, ignores him. The good young man, once again slices off the head of a beloved pet with his sword. He feels a bit bloody now and casts about for someone else to boss around. He decides to ask his only horse to fetch his water to wash all this sticky blood off his hands. Naturalmente, the horse gives out quite the whinny when his head is lobbed off by the good young man.

Bad hombre?At this point, my earlier doubt about the use of the descriptive “good” as applies to this young man of little cash seemed well-founded. If he is considered good in 14th century Spain, what would the bad hombres have had to be doing in comparison? All along in this narrative, the young bride says nothing. I anticipated she would show her bravery and strength by whacking him over the head with a heavy-duty frying pan for the slaughtering of his animals. I expected her to at least rise up and tell him he is a lunatic and is leaving with her head and her money. But no. That is my 21st century feminist fury speaking. She, a 14th century woman, is neither brave nor strong…yet. I feared it would take seven centuries before she could display these fine qualities.

The bloodbathOf course, you might see where all this had been going. The good man then asks his new wife to fetch his water, and she, shell-shocked from all this violence, gets it for him. They retire and she emerges next morning obedient and happy for having been subjected to the bloodbath of the night before. For what else says happiness than being traumatized by a madman into handing over your fortune and becoming his terrified slave? And they lived happily ever after…until about three months later when he gets rip-roaring drunk and passes out on the living room sofa. (I added that last bit). You can fill in the rest.

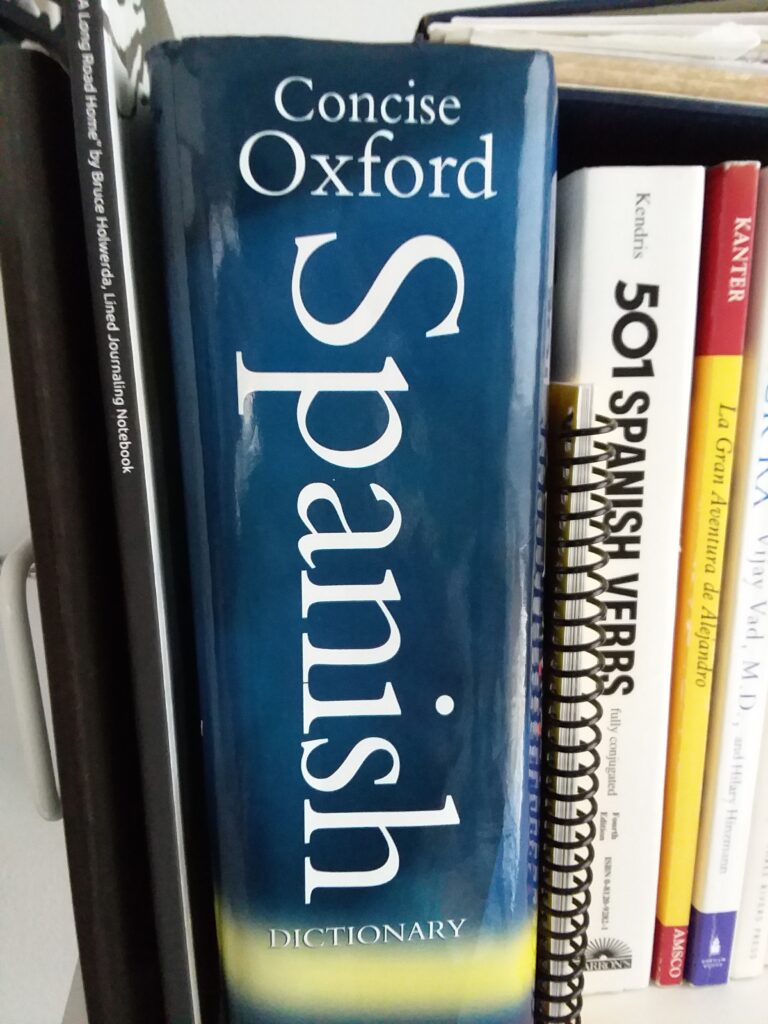

I keep it handy!Where did I go wrong in my understanding of the title? What happened to the strong, brave woman? I had no doubt that such a woman could exist in any century, though her attributes might be displayed in a different manner than we think of today. I turned to the English translation for guidance. Una mujer muy fuerte y muy brava, translated from the words of an early 14th century folklorist, actually meant, in his mind: a very wild and unruly wife. I scrambled for my Spanish dictionary since my understanding of the language is rather rudimentary.

And yes, way down the line from the general meanings, this interpretation can be used to describe a woman. Though un hombre muy fuerte y muy bravo means just what I think it does, though fierce may be substituted for strong. Fierce women, it seems, were considered unruly in the days of Don Juan Manuel. I’m glad my book had an interpreter to sort these things out for me.

I am ecstatically happy to be living in the 21st century, where a woman can be fierce and brave and be admired for it. Just last week, as I watched the swearing in of the first woman vice-president in our American history, I felt some vindication for the woman who was married by that stinker for her money. I told you it would be 700 years before she arrived. But, I have saved one last surprise for you. The end of the story.

It seemed the elder, good (the word good being relative both then and now) rich gentleman is somewhat impressed by the dubious tactics of his slimy son-in-law. He ignores the horrifying situation his daughter has endured, admiring only the outcome of a cowering, obedient wife. At breakfast, he asks his wife to bring him water to wash his hands. She tells him to fuck off. There she is! So, maybe not 700 years after all. Don Manuel has been redeemed.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Note: The Feminist Quarterly is a never-ending bitch-fest detailing all the bullshit manifested by a very long patriarchal domination of human life. When interviewed, Kamala Harris, Vice-President of the United States, declared “Your 700 years are up!” (not really, she could not be reached for comment on this blog post, but the declaration, as does the commentary used to describe the above story, still live in my imagination).

Stay fierce good women,

Cheryl

Guest Editor Anne is my guru of grammar, my queen of quip, my wizard of words. Really, she could red-pencil all my stuff and still make me laugh!

I worked in a day care with a lot of native Spanish speakers. I had a working knowledge of Spanish. Now that I don’t work there anymore, I know just a little Spanish. I’m good at accents, though!

Bravo to you!

You’ve hit the problem square on the head. Since I moved from Texas I have no Spanish-speaking buddies to chat with, so my usage has dwindled. I would love to hear your accent.

What a great retelling! I’m freshening up my Spanish using Duolingo. I have yet to try reading the stories. Maybe some day, with dictionaries in hand, we should have a zoom conversation in Spanish only! 😃

Yes! I need a new translating app on my phone. The last one seems to no longer be working. Try the public library for kiddie books. Here’s my favorite thing to say in Spanish: Espero que tengas un buen dia.

What a brilliant idea to read children’s books written in the language you’re studying! Hmmm, I wonder if Dr. Suess’s stuff has been translated into other languages.

I’m willing to bet that Dr. Seuss has been translated into many languages. I have read a few of his in Spanish. The public library has books in foreign languages, but I sometimes take too long to finish them! Thanks for reading the blog!

You’ve perhaps uncovered the story that inspired Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew.” Despite being billed as comedy, his play is misogynistic to its core.

Yes, the notes suggested that Shakespeare did indeed use this story as a basis for Taming! Good catch!

It was an honor to be guest editor for this sterling masterpiece!

Ah, such wonderful flattery. I live for it! Just kidding. Thanks for all your help and support!